Democratizing policing in Kenya: Are we “Waiting for Godot”?

by admin on | 2025-10-02 11:04:47 Last Updated by admin on 2026-02-20 20:21:15

Share: Facebook | Twitter | Whatsapp | Linkedin Visits: 312

In the play “Waiting for Godot” the Irish playwright Samuel Beckett tells the story of Vladimir (Didi) and Estragon (Gogo).1 The two characters spend endless days waiting for someone named Godot, whom they believe will provide them with salvation. As they wait for Godot, they pass time with conversations, physical routines, and philosophical musings. But Godot, the savior, never arrives. For more than two decades, we have been trying to reform policing in Kenya, hoping that our Godot, that is democratic policing, will arrive and save us from tyranny. And in the process, much Like Didi and Gogo, we have engaged in all kinds of conversations, the routines of taskforces, and philosophical musings on what to do with our policing, hoping that it will become democratic. But it never does In this key note speech, I would like to use the lens of administrative law to reflect on how a democracy should be policed, how Kenyans are policed, why it is difficult to reform policing in Kenya, and how we might be able to democratize our policing. We cannot, and will never be, free unless and until we democratize our policing. Towards this end, I would like to contend that carefully designed structural interdicts offer perhaps the only viable institutional mechanism for democratizing policing in Kenya. II. How Should a Democracy Be Policed? The main work of the police is to enforce the criminal law, so that crimes are prevented and social order is maintained. To enable the police to do this work, the law grants them extraordinary and often discretionary powers to use physical force, investigate, arrest, and detain accused persons. But these discretionary powers can be abused, thereby compromising the liberties of individuals and compromising the effectiveness of policing, given that citizens who consider that the police are abusing their powers will not cooperate with the police. For these reasons, policing needs to be democratic, meaning that policing policies and practices should be formulated and implemented through processes that are participatory and accountable. Since the criminal law is characterized by discretionary judgments, there is a need for public participation and accountability in policing decision-making, in terms of the making of policing policies and rules and oversight of policing practices. There are two ways of governing policing. On one approach, the law grants the police discretionary powers to enforce the criminal law and lets them get on with it. On this ex post approach, in which criminal laws typically comprise vague offences that confer on the police blanket authorizations, civilian review boards and courts only intervene to correct instances of abuse of power and police malpractices or methods after they have occurred. This approach is designed to address individual instances of police misconduct as opposed to addressing the governance shortfalls that produce such misconduct.2 On the second, or ex ante approach, the law attempts to circumscribe the powers of the police by requiring public rulemaking (that is, public participation in the making of policing policies and rules) and democratic input or oversight in the implementation of policing policies and rules.3 On this approach, laws and institutional mechanisms enable citizens to observe and scrutinize the substantive and procedural policy choices of criminal law enforcement. The ex post approach has been the dominant governance model, the claim being that policing is unique and cannot be treated like other agencies of executive government. A common justification here is that confidentiality in policing “is both necessary and appropriate”.4 Thus, it is claimed that making policing transparent would “allow criminals to more skillfully evade police detection.”5 As a result, police exceptionalism has meant that policing agencies are simply authorized to enforce the criminal law and determine what enforcement actions they can take, without the public interrogating the rationality of policing policies and methods.6 Hence, compared to other agencies of executive government, the public often do not participate in the making of policing policies and rules, and the police often do not have to justify their policing methods and practices. The consequence is that the police largely get to do what they want, when they want read more...

Search

Trending News

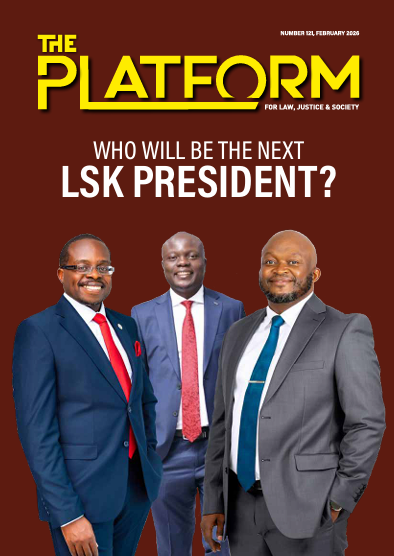

Who will be the next Law Society of Kenya President?

Who will be the next Law Society of Kenya President?

The Forgotten titan: Why Talanta Stadium should Honour Kenneth Matiba

The Forgotten titan: Why Talanta Stadium should Honour Kenneth Matiba

The guardians of justice have crossed the political line: A Constitutional reckoning for the Judicial Service Commission

The guardians of justice have crossed the political line: A Constitutional reckoning for the Judicial Service Commission

Extrajudicial killings: A blatant violation of constitutional and human rights

Extrajudicial killings: A blatant violation of constitutional and human rights